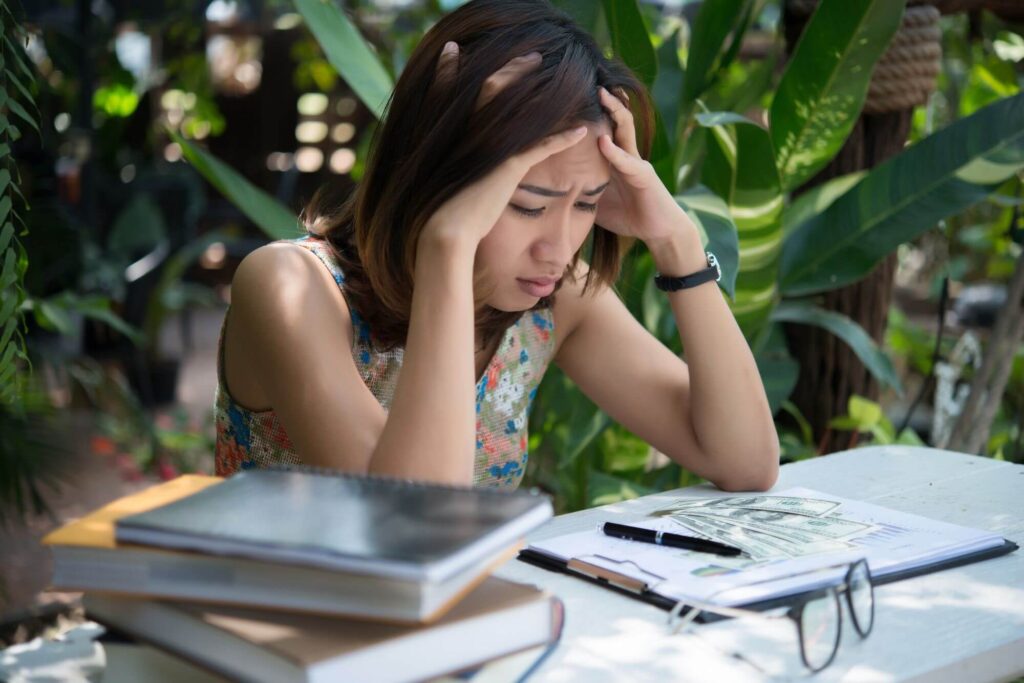

Ever wondered why you feel a pang of guilt splurging on that luxury item, while your colleague invests in stocks without batting an eye?

In the bustling corridors of our offices, amidst the hum of keyboards and the aroma of freshly brewed coffee, there’s a topic that often remains hushed – our relationship with money. But why should we, as professionals, care about this seemingly personal matter? Linda, a clinical psychologist at Intellect, prompted us to reflect on a crucial question: “What are your money narratives?”

Coined by financial psychologists Brad Klontz and Ted Klontz, “money narratives” are the beliefs we hold about money that underpin our financial behaviours. Linda explains, “It’s not merely about the digits on our paychecks or the figures in our bank statements. It’s the profound tales we narrate to ourselves, tales that influence our choices, dreams, and even how we value ourselves.”

Let’s delve into the four money narratives we may unknowingly adhere to.

The four money narratives

1. Money avoidance

Sarah, a gifted professional, turned down a high-paying role at a prestigious firm. Raised with a suspicion towards wealth, she grew up hearing “money corrupts” and feels wealth might distort her true values. This belief led her to prioritise inner peace over a higher salary. She may think:

“Wealth corrupts and life might be better with less money.”

“People get rich by taking advantage of others.”

“Being rich means you no longer fit in with old friends and family.”

“It is hard to be rich and be a good person.”

2. Money worship

Raj, an enterprising individual, tirelessly seeks the next big break. Driven by the notion that hitting his financial target brings ultimate joy, he often sacrifices personal time. Stories of a prosperous relative reinforce his belief in money as the universal solution, even if it compromises his wellbeing. He may think:

“Money is the solution to all problems and the true path to freedom.”

“Money is what gives life meaning.”

“It is hard to be poor and happy.”

“Things would get better if I had more money.”

3. Money status

Living in a vibrant city, Emily projects an opulent lifestyle online. Yet, she’s battling credit card debts. Influenced by a community that equated worth with material wealth, she feels pressured to portray affluence, even if it means overspending. She may think:

“My self-worth is directly linked to my financial standing.”

“People are only as successful as the amount of money they earn.”

4. Money vigilance

Alex, with a stable job and savings, dreads spending. He recalls his grandparents’ frugality during tough times and remains apprehensive about potential financial crises. This narrative makes him value caution over enjoying his earnings.

“Money must be guarded and handled with caution.”

“It is important to save for a rainy day.”

It’s worth noting that these narratives are neither objectively good nor bad. Importantly, consider whether they are serving your current circumstances and future goals. For example, a vigilant money narrative may have helped you with your student loan, but clinging onto it even after clearing your debt may cause undue stress.

What is your money narrative?

But how do we uncover these narratives, especially when they’re so deeply embedded in our psyche? Linda suggests a powerful tool: reflective questions. Pause for a moment. Ask yourself, “What did money mean in my household growing up?” Your answer might surprise you.

By asking ourselves questions like, “How was money discussed in the family?” or “How do I feel when I can’t afford something I want?”, we can start to gain insight to the financial beliefs that drive our behaviours. Are they serving our current goals? Or are they remnants of past beliefs that no longer align with our aspirations? By understanding and, if necessary, reshaping these narratives, we can not only make sound financial decisions but also enjoy better relationships with others.

In the workplace, understanding these money narratives helps to foster a culture of well-being, where discussions about money are rooted in empathy. Rather than labelling an employee as “stingy” for not wanting to contribute to a farewell gift, we can simply acknowledge that other financial priorities take precedence for them and respect their decision. In the end, our financial decisions are not just about “maths alone,” as Linda puts it, but are deeply intertwined with our identity, upbringing, and life goals.

How to talk about money

1. With your partner

Navigating financial disagreements in relationships can be challenging. Often, the stress isn’t just about the money but the deeper narratives and beliefs we hold about it. When addressing these disputes, it’s essential to approach the topic with curiosity rather than judgement.

Instead of pointing fingers, delve into the underlying money narratives influencing decisions. For instance, rather than saying, “You need to stop buying handbags,” consider asking, “How do you feel when you buy a new handbag?”

This approach, recommended by Linda, shifts the conversation “from a blame frame to an aim frame,” promoting open dialogue. For example, discovering that your partner shops to de-stress may help you approach the conversation with more compassion. For all you know, you could even brainstorm for other means to that same end.

Remember, the goal isn’t to change your partner but to understand them, ask for their opinion, and find common ground.

2. With your friends

We’ve all been there: friends are planning an exciting trip or a night out, but the budget just doesn’t allow for it. Addressing this can be awkward, but open communication is vital.

Honesty, paired with a proactive approach, is the best policy. Instead of avoiding the topic or making up excuses, be upfront. Let your friends know you’d love to join but are currently watching your finances. Proactively suggesting alternatives, like a walk in the park or other budget-friendly activities, can ensure the focus remains on quality time together, not the money spent.

3. With your children

Imparting financial wisdom to our children is crucial. But as Linda highlights, “A lot of times, our money behaviour is driven by this narrative that we’ve picked up.” So, how do we ensure we’re not passing down unhelpful generational money habits?

Engagement is the key. Children learn best when they’re engaged, so introduce financial concepts through interactive games. For instance, you could set up a “store” at home where children can “buy” toys using play money earned through chores. This not only teaches them the value of money but also the importance of earning and saving.

Lastly, encourage open conversations about money. Ask them reflective questions, like “How do you feel when you get your allowance?” This helps them recognise and understand their own budding money narratives.

Unlocking financial wellbeing with Intellect

Whether you’re an individual seeking clarity or a company leader who sees the value in financial wellbeing, Intellect is here to guide you. For starters, our team of experts, led by professionals like Linda, offers tailored sessions for your employees to develop self-awareness.

As part of our holistic wellbeing offering, Intellect has also partnered MoneyFitt, a Singapore-based FinTech platform that empowers individuals to take control of their financial wellness by offering personalised tips, a network of trusted experts, and a wealth of educational resources.

Just as Intellect takes pride in providing personalised mental healthcare, MoneyFitt also understands that every employee possesses distinct financial needs and aspirations, and is seeking specific, actionable measures customised to their unique financial circumstances.

Learn more about Intellect EAP today.